Trauma-Informed Teaching: 8 Strategies to Fostering a Feeling of Safety

Students can’t learn unless they feel safe. When it comes to student trauma, there is much that is beyond educators’ power, but there is also a great deal they can do to build a supportive and sensitive environment where students feel safe, comfortable, take risks, learn, and even heal.

– Jessica Minahan

INTRO

Being trauma-informed in schools is essential because many students carry the invisible weight of past experiences that can impact their behavior, learning, and emotional well-being. Trauma affects brain development, making it harder for students to regulate emotions, build relationships, and focus in class. Without understanding these effects, educators may misinterpret trauma responses as defiance or disengagement, leading to punitive discipline rather than meaningful support. A trauma-informed approach fosters a safe, predictable, and supportive environment where students feel valued and understood. By recognizing the impact of trauma and responding with empathy and effective strategies, schools can help students build resilience, improve academic success, and develop the social-emotional skills needed to thrive.

OBJECTIVES

- Recognize the impact of trauma on a student’s learning experience.

- Learn and apply trauma-informed strategies.

- Implement trauma-informed practices to create a supportive school environment.

Trauma affects the body in many ways, activating areas of the brain that influence behavior and forming new neural connections that may not be ideal. Trauma triggers can vary widely—from a smell, color, noise, or more. These triggers differ from person to person, and individuals may not always be aware of them. When a student experiences trauma and triggered in the classroom, it effects their learning. As educators, it is important to recognize that not all behaviors are rebellious; some may be a response to perceived danger, even when no real threat exists.

Watch Dr. Nadine Burke Harris’s Ted Talk as she explains how the repeated stress of abuse and neglect has real, tangible effects on the development of the brain.

As educators, it’s essential to recognize how trauma can affect a student’s learning and behavior. Not all behaviors are acts of defiance; some may be protective responses to perceived threats, even when no actual danger is present. Angry outbursts, difficulty concentrating, and frequent absences may all be signs of trauma. It’s also important to remember that students may respond differently to similar traumatic experiences—what one student expresses through anger, another may internalize through withdrawal. By recognizing these varied behaviors, creating emotionally safe spaces, and collaborating with mental health professionals, we can more effectively support students in both their academic and personal growth. The National Child Traumatic Stress Network offers a valuable toolkit to help educators identify trauma responses and implement supportive strategies.

Building on this understanding, the article “Trauma-Informed Teaching Strategies” by Jessica Minahan, published by the Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development (ASCD), outlines eight practical approaches educators can use to better support students impacted by trauma. These strategies offer small, meaningful shifts in practice that help create a learning environment where all students feel safe, supported, and ready to engage.

8 Trauma-Informed Teaching Strategies

Expect Unexpected Responses

When a student is triggered, their response may seem abrupt; however, educators should avoid taking it personally and instead consider the context underlying the student’s reaction.

Employ Thoughtful Interactions

Teachers who build safe, supportive relationships and employ thoughtful, responsive communication strategies can significantly improve behavior and learning outcomes for students impacted by trauma.

Be Specific About Relationship Building

Clearly outlining and sharing relationship-building techniques among staff can enhance student behavior and help students remain in class by ensuring consistent adult support.

Promote Predictability and Consistency

Providing predictable schedules, routines, and positive attention helps students affected by trauma feel safe, reduces anxiety-driven behaviors, and establishes teachers as reliable and supportive adults.

Teach Strategies to “Change the Channel”

Teachers can support students by explicitly teaching cognitive distraction techniques—strategies designed to intentionally redirect distressing thoughts and help students manage unwarranted or troubling thought patterns.

Give Supportive Feedback to Reduce Negative Thinking

Students impacted by trauma often interpret neutral or mild feedback negatively, so teachers can support them by explicitly express positivity and use techniques like the positive sandwich approach when providing corrections.

Create Islands of Competence

Teachers can support students who have experienced in developing a positive self-concept by intentionally creating opportunities that highlight students’ strengths, enabling them to experience success and build optimism for their futures.

Limit Exclusionary Practices

Behaviors communicate messages, and common disciplinary practices—like ignoring misbehavior or using conditional rewards—can unintentionally reinforce feelings of neglect or rejection in traumatized students; instead, fostering trust through validation and consistent, unconditional support is key.

How else to support students impacted by trauma?

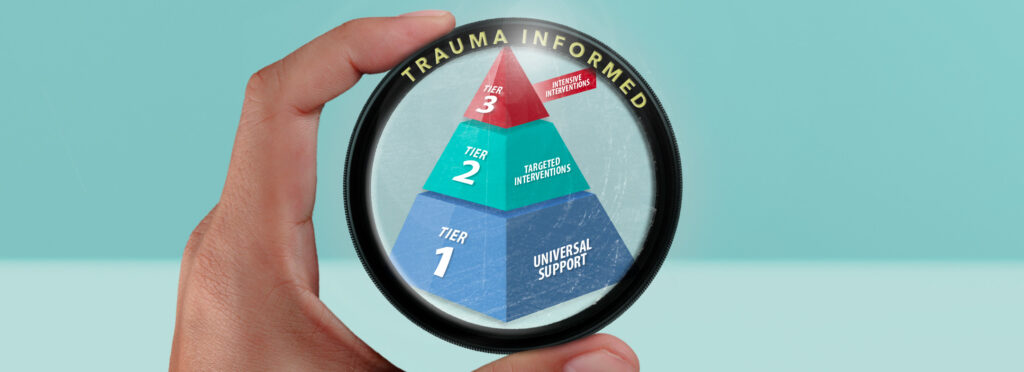

The article “Teaching in a Trauma-Sensitive Classroom“ by Patricia A. Jennings highlights the importance of recognizing and addressing trauma in students to create a supportive learning environment. It explains how adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) can negatively impact students’ behavior, emotions, and ability to learn. Trauma-informed schools train educators to recognize signs of trauma, respond with empathy, and implement strategies that foster safety, trust, and resilience. By prioritizing relationships, emotional regulation, and supportive discipline, schools can help students heal and succeed academically and socially.

Stay in the Loop

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Responses